COLIN MANNINGS - FIRST TRIP

My total career at sea spanned 11 years and I served in the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Mediterranean and India.

On my first trip we nearly ran out of coal dodging the Bismarck following RN instruction. The trip ended badly when at 1740hrs on the 29th June 1941 the S.S. Rio Azul was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-123 about 200 miles southeast of the Azores whilst on voyage from Pepel via Freetown to Middlesborough with a cargo of iron ore. She broke in two and sunk within a minute. The Master, 31 crew and one gunner were lost. The survivors, 6 crew and 3 gunners were picked up from rafts by HMS Esperance on the 14th July and taken to Scapa Flow, Orkneys.

The following are extracts from the log of time on the rafts written up on HMS Esperance:

The Rio Azul 4,000 gross tonnage with a cargo of iron ore was torpedoed on June 29th 1941.

The torpedo struck the ship on the port side beneath the bridge smashing to port lifeboat and breaking the ship in two at this level. The bows and stern cocked in the air and she sank within a minute. There was no opportunity of lowering the starboard boat as the falls had gone over the side and there was no slack to pay off. All that was left to do was to jump for it and hope to pick up one of the rafts.

Shortly after the ship sunk a fairly large U-Boat surfaced within 100-300 yards distance. She appeared to be in excellent condition, the paint was new and it was the general opinion that she was fairly recent from the shipyard. Two guns were mounted, one forward and one aft, the size of which was not determined. The officer in charge made it clear that he would attempt to send some assistance and proceeded without leaving any supplies.

By nightfall 18 men had managed to climb onboard the rafts including the 3rd Mate, Senior Radio Officer, Chief Steward, Apprentice, Boatswain, two soldier Gunners, Merchant Navy gunner, three Seamen, Cabin Boy, Galley Boy, two Greasers, a Fireman and a Trimmer. Shouting was heard but no other survivors could be found and rescued. Some who could not be identified hung on to the spars and other pieces of floating timber for a while but had drowned before they could be reached. One of the rafts was badly damaged and one of the supporting drums at one end had come adrift leaving a sloping surface. The other was intact and kept the majority of the other survivors afloat. From amongst the wreckage it was possible to save a tin containing about ten tablespoons-full of molasses, a tin of egg substitute and a tin of cocoa. In addition to this tins of cigarettes and tobacco were salved but there were no matches.

There was one and three quarter gallons of fresh water remaining which was secured on to the rafts. Flares and distress signals had been destroyed at the time the raft was launched.

The water was rationed, the daily allowance being the amount what could be contained in the brass stopper of a paraffin can, representing about three teaspoons-full. The molasses, egg substitute and cocoa was issued on a stick moistened by a little fresh water. One night there was a shower of rain and it was possible to collect a gallon of water by means of a tarpaulin which was spread out. This was all the food and water available for the 18 survivors.

On the fourth day a ship was sighted, probably only a tramp, although only the masts, bridge and funnel were visible. Despite the flashing of cigarette tins in the sun, the idea of the Boatswain, and the waving of a flag on an improvised flagpole, the raft was not seen and the ship proceeded on her way.

The posture on the raft was very cramped, and the only means of stretching the limbs was to bathe. This was done daily by all with the exception of the Chief Steward whose age was 69. Black fish were seen but no sharks. It was found helpful to sprinkle water on each other, and this was done at frequent intervals. Opinion is not unanimous as to the assistance afforded by drinking urine a practice which was regularly employed by some of the survivors, but it was agreed that drinking sea water was definitely harmful. As far as possible attempts were made to conserve energy and we lay as still as possible for long periods. We slept fitfully but our sleep was usually accompanied by some dreams of a fantastic type. Prayers were said daily. There was no undue despondency and for the most part the craving for food and water was not as marked as might have been expected. During the last few days we were over-whelmed by a rapid and progressive weakness and sensibility to the various discomforts became dulled.

It was not until July 11th, the 13th day, that the Radio Officer the first to die, succumbed; he was followed the next day by the Chief Steward. On the 13th there were three deaths. One of the army gunners who had been drinking sea water and his urine, and whose mind became somewhat deranged, went over the side for a swim and was unable through weakness to return to the raft; the Cabin Boy and a Trimmer passed quietly away. In the early hours of the 14th, the Third Mate who had gone crazy, and later it was found that one Sailor had died.

Without a doubt it was the flashing of the tobacco tins which attracted the attention of the look out on the ship that led to their rescue.

Photograph taken from HMS Esperance shows the survivors about to be rescued.

I had to leave the MN following the sinking as I developed Asthma which became worse after spending 15 days in the sea clinging to a raft. After some time in hospital I was given a 100% pension but this was reduced and later stopped, as I had not made myself available for further medical examinations. I had become bored being at home and had gone back to sea. I joined R. Ropner Co. as an apprentice.

I was in Malta in 1943 on S.S. Fort Cadotte when we were informed all ships in harbour had to get to sea as quickly as possible as the Italian fleet was making its way towards Malta. We were in Malta for repairs and the boiler was shut down which in a steamship means it takes hours to get sufficient steam up to move. Fortunately the Italian fleet surrendered before it reached Malta.

Whilst in Bari, again on S.S. Fort Cadotte, on the east coast of Italy, the Sam boat in front of us carrying a cargo of high explosives blew up. This shattered the harbour, which was out of commission for about three days and badly damaged the ship I was on and we had to go into dry dock in Alexandria and so we missed the second front.

Then we were sent to India.

Colin Mannings No. 94

June 2020

COFFIN SHIPS.

By

Malcolm H. Mort.

Having successfully completed the Advanced Marine Automation and Control training course at a Maritime Technical Training College, I later attended the Head Office for an interview with the Personnel Manager of the Shipping Company employing me. He congratulated me on my success and said that the Engineering Superintendent, due to me being very conscientious and having a good sense of humour had decided to send me to the MV Chelsea Bridge as the Electrical Officer when it returns to the UK in a couple of weeks.

The Electrician laughed, and said, “We have been down that filthy, stinking oily hole since 4 O’ Clock this morning jacking the big ballast and pumping out valves open and closing them with this hand operated hydraulic pump. I have a long journey ahead of me to Glasgow and feel bloody knackered, with being soaked in sweat in this damn tank suite. I’m going to get this damn thing off and have a shower and then I’ll show the new Lecky the Engine Room Main Switch Board and Control Console as soon as he has signed on. I will be catching the first available train to Glasgow with my resignation as, I’ve got an offer of work on the Oil Rigs with better money and a lot less trouble. Come to think of it, did the Engineering Superintendent tell you about the Duct Keel Electro-Hydraulic Pumping System persistent low insulation problems,” He asked?” I answered, “All he said, was it was controlled from the engine room console by following the pipe line diagram and operating the switches and looking at the signal lights showing when the valves were being opened or closed”. It’s as simple as following a road map. The Chief Engineer remarked, “The 3rd Engineer who knows the hydraulic system in the Duct Keel is staying on for a few more months as he needs more money to get married before their child is born. The electrician laughed and said, “I can’t see that happening with all that he drinks in the lounge when we are playing bridge and drinking in rounds. The other thing is, by not mixing and playing cards, is the lonely life of sitting alone in your cabin trying to handle the stress of this job. To add to the noise and engine vibration, which you even feel in your bunk, there is the noise of the plates, cutlery and glasses rattling on the saloon tables. Then there is the feel of the power thrust each time a cylinder fires with a bloody great shuddering thud. The other annoying thing is the engine room alarm system and control console with the dater logger, with every alarm repeated in our living accommodation and on the bridge. Although ship owners installed automation to save money by reducing crew sizes, they failed to consider the stress it placed on the electrician and other engineers with specialist knowledge when the automation sometimes gave false alarms due to moisture in the atmosphere, which is one of the problems with electronic systems together with vibration and high temperature changes. The Chief Engineer commented, I’m nearly beyond such concerns, as I’ll be handing over to my relief Chief Engineer as soon as he arrives. The 3rd Engineer who is staying on will introduce Malcolm the new Lecky to the duct keel after he has signed on. I have to go down to the engine room to see how the Second Engineer is getting on with removing and lifting No 3 Cylinder connecting rod from the crankshaft and chaining it up inside the engine. Tomorrow morning we are sailing for Pepel in Sierra Leone on 9 cylinders at 70 Revs per minute to load iron ore for Japan.” “That’s slow,” I commented for a big beast of an engine like ours.” We usually run at about 108 Revs to stop the exhaust manifold temperature from rising too high, said the Chief Engineer.

Suddenly the Ships Master came in to the lounge accompanied by someone from Immigration and asked us who were signing on to individually approach the table where he and the immigration man had now sat down. Within a few minutes I had signed on as the Ships Electrician and then quickly introduced to the electrical layout before being handed a Green PVC Tank-suite by Donald to be taken down the Duct Keel for a detailed introduction. Suddenly the ships Master called the Chief Engineer to the table and told him that the company wanted him to stay on the ship until the crankshaft had been repaired in Japan and then fly him home on leave. He wasn’t very happy, but he was a company contract man who was buying his house on the company scheme. As you can see said Donald the Southern Irish 3rd Engineer, this deck hatch in front of the aft engine room and living accommodation is the aft entry down a long vertical rung ladder to the Duct keel, which is a long passageway carrying the electric cables, water and oil pipes from the engine room forward bulkhead to the forecastle. It is a very dangerous place at the bottom of the hull to be in. As two people have already lost their lives by being overcome by gas fumes, I am showing you the safety procedure you must follow. Firstly, you open this hatch cover and secure it open. The next thing is to switch on the Duct Keel ventilation fan for at least 20 minutes. You must never attempt to climb down the long ladder to the void spaces between the holds at the bottom of the hull without having a safety line attached to you and somebody standing at this hatch the whole of the time you are down there. You must use the gas-testing detector, which “Bleeps” if it is unsafe to open the Duct Keel Door. Slightly crack the door open and test before fully opening it. Then test again before fully entering the Duct Keel tunnel. While you are in the Duct Keel the fan must not be switched off and the person must not leave the deck entry hatch. Just before he entered the hatch, he told the Engineering Cadet Apprentice that we would not be down there long and asked me to stay where I was until he called me from the bottom of the ladder. Within 35 Minutes we were back up on deck again and then had a shower followed by a couple cans of Larger from the bar with the new Chief Engineer, and the people who were waiting for the arrival of Taxi’s to take them to the Railway Station to catch their respective trains home. During the conversation between the new Chief Engineer, named Mr John Roberts and the one who was leaving, the question of failing to pump out the duct keel arose. John Roberts laughed and said “In that case I would be the first in the motorised Lifeboat and leave Lecky and the 3rd Engineer to swim for it. The 3rd Engineer laughed, “Only if this damn thing does not sink before getting the bloody Lifeboat engine started.” The Chief Engineer said, “I’m sick and tired of the frequent mechanical breakdowns with the bloody 16 hour field days as we call them giving us precious little time to relax. It worries me when I feel so bloody tired as I walk around the engine room thinking that I need a couple of matchsticks to prop my eyes open, hoping that we will be able to arrive at our port of cargo discharge or loading at the specified time.” The 3rd Engineer laughed and said, “It’s a case of six days shalt thou labour and do all thy work. On the seventh day thou shalt get thy backside down the engine room stairs and do even more.

At 10 am the following day the Pilot came on board and with the Master and Chief Engineer being satisfied with everything, we sailed until we discharged him into the Pilot boat alongside of us. The engine room telegraph sounded and its pointer moved to Half Ahead, I moved the telegraph handle to acknowledge the signal, allowing the Second Engineer to restart the main engine and bring its speed up to 60 RPM as I wrote this occurrence in the Telegraph Log Book with the time showing the full away start of the voyage. At lunch time I came up from the Engine Room, had a shower and changed into my uniform to have my lunch in the saloon, to the sounds of the thudding of the main engine together with the rattling cutlery, drinking glasses and plates. Later I felt the vibration when lying on my Day bed or on my bunk. It was something I would just have to learn to live with. Which left me wondering what it would be like with the main engine running at 108 Revolutions Per Minute. On the third morning of our voyage the main engine sudden suddenly stopped without the warning of the alarm panel indicating the possible cause. The attempts to restart it by the Chief and Second Engineers proved futile. Then up went the battle cry of “Lecky”. All faults are electrical until proved otherwise. Looking up at the telegraph I noticed that the indicator was not indicating anything. So I telephoned the Bridge and was told by the 3rd mate that their Telegraph Indicator was pointing “Full Ahead.” I told him that I would be up on the Bridge with my small tools in a couple of minutes. When I arrived on the bridge and told the Master I’d have to take the cover off of the telegraph. He asked if I knew what I was doing. I smiled and said, not until I’ve looked inside. With him standing over me with a very concerned look as I removed the cover, looked inside and said, “What is this I see before my eyes, a little Selsyn which appears to have lost its pinion gear. Feeling carefully around the inside base of the telegraph I found the gear and three little instrument screws and said to the Master, “Now for a bit of electro trickery and suggested that the 3rd Mate telephoned the engine room and relayed what they told him to me. I offered the gear to the Selsyn with two screws, screwed in to its boss by three threads, so I could waggle it about a bit, leaving our telegraph on full ahead. I told the 3rd Mate that I was meshing this gear tooth by tooth until the engine room pointer read the same as the bridge with an engineer telling him over the phone what I was achieving until I got the both pointers synchronised. I then put the third screw in and tightened them all up, tested the telegraph and replaced the cover. Since it worked all right the Chief Engineer re-started the engine and got underway again within an hour. The Master said Thank God you knew what to do. I was concerned about us drifting around out here and needing Tugs with this damn great thing. If you had not fixed the Telegraph, I shudder at the thought of the costs.

A few weeks later we arrived at Pepel in Sierra Leone to load our iron ore cargo for Japan which passed without any problems, except for the engine noise and vibration in our living accommodation persistently annoying people by causing sleep loss, which made some of our Chinese crew members tired and a little short tempered. In due course we arrived at Kobe and had our crankshaft repair done quickly and efficiently without having the crankshaft removed from the ship. We then sailed to the designated berth and discharged our cargo. Unfortunately when the crane driver was lifting a Bulldozer out of one of the holds and was turning the crane to put the bulldozer down on the dockside, the Bulldozer struck the hatch structure surround one hold causing considerable damage which they were unable to repair, compelling us to go elsewhere to get it repaired. After the repair we went back to Pepel to load iron ore for Port Talbot. However on the way to Pepel we had a problem of water flooding the Duct Keel which caused low insulation to the electro hydraulic pumping system, compelling the 3rd Engineer and I to spend considerable time working in the Duct Keel to pump out water ballast to be able to load our cargo at Pepel. During the voyage, one of our Alternators caught fire and the rotor burned out. This matter being handled by an Engineering Superintendent in the main Office, told the Chief Engineer by phone to have it stripped down by me and landed ashore on arrival at Port Talbot.

After discharging our cargo at Port Talbot, we sailed for Pepel with our very disappointed Chinese crew who had been expecting to be relieved on our arrival, claiming to have done their service time. In effect their sense of goodwill ran out when they threatened to go on strike unless, they were discharged and repatriated from Pepel because they thought the ship was, noisy, much vibration and Jinxed.

From what I remember we had arrived at Pepel and started pumping out our ballast when the valve system failed, resulting in the 3rd Engineer and I having to go down the duct keel with a tool to open the valves manually. We came up from the duct keel at breakfast time, and after having a hot shower in the engineers working shower outside the engine room door, I changed my clothes and went to my cabin. There I met the Chinese Chief Steward, who started shouting at me about the way “British Officers were treating poor Chinese crew who were on strike.” Then he raised his arm in temper to strike me. I grabbed hold of him and threw him out of me cabin, leaving him lying on the floor, before closing the door. A few minutes later the Master and Chief Engineer came to my cabin and asked me to join them at a crew meeting on deck. To my surprise the catering staff were at the meeting with knives, a machete, a hammer, chipping hammer. The Master asked me to publicly apologize to the crew for hitting the Chief Steward. This I did willingly and offered to shake his hand, which he rejected. It was then the second cook asked what was going to happen to me. The Master told them. I was being sent home to face an inquiry. I then went to my cabin with two engineers with orders to remain with me while I packed my bags. We were told not to unlock the door unless the Master and Chief Engineer were together. Before leaving the ship I learned that one of the cooks leading the strike had political significance where the crew were concerned. Eventually a taxi arrived and I left the ship with the engineers carrying my luggage. It took me to a Diesel Locomotive shed were I climbed into the drivers cab with the driver of a very large twin bogey diesel electric locomotive which took me to a waiting taxi about an hour travelling distance away. From there another taxi took me to the airport. Within 2 hours I was onboard a plane flying home.

At a later date my sacking case was heard by a Merchant Navy Tribunal with the Merchant Navy and Airline Officers Association representing me and resulted in my acquittal.

This incident did no damage to my career prospects because my next employer was P&O Bulk Shipping Division as an Electrical Officer on the SS Ardtaraig which was a very large 28,000 SHP Steam Turbine powered Super Tanker with an Unmanned Engine Room. In particular it had an emergency alarm panel in our cabin area, which we found stressful with its bleeps on various occasions during the night leading to people waking up after dreaming the alarms were sounding. However during this voyage the 500 HP electric boiler fan caught fire and burnt out and we were compelled to keep watches as we were compelled to reduce speed and rely on the 300 HP fan until we were able to get the motor sent ashore and rewired. I lost the help from the Second Electrician with the daily planned maintenance work I was doing and got behind with it because I ideally needed a person with electrical experience to do installation testing while working apart from each other.

Such was the tension on some people’s nerves. This raises the point about the honesty of a personnel officer who is looking for a crew for an unpopular ship with a high turnover of crewmembers. The reality of life being that this person can only be as honest as he needs to be in the circumstances to allow him to keep his job.

As things turned out for me I was discharged from the Merchant Navy in October 1975 as being unfit for further seagoing service as a 3rd Engineer due to the onset of Arthritis in the lower part of my spine. After attending an Engineering Management Resettlement Course at the Polytechnic of Wales I was issued with a green disability-working card and employed by a Cardiff firm of Aeronautical and General Engineers as an Engineering Inspector working on MOD Radar and Jet Engine Test Beds, manufacturing and maintenance contracts to Def Con 0521.

About that time I discovered that very large ships like the Chelsea Bridge, Kowloon Bridge and the Derbyshire were being referred to as: Coffin Ships. However the name Chelsea Bridge was changed to Iron Sirius and she was transferred to an Australian Management Firm and then sailed under the Australian Flag.

Before going to sea I was as a Certificated Mines & Quarries Colliery Electrician and was working on the night that a Miner was killed in a Coal face by a roof fall. The walk with all of us behind the stretcher treading our way up a very steep incline at Nantgarw Colliery, Mid Glamorgan is something I have never forgotten. The sight of these very large so- called monster coffin ships can be seen anchored awaiting loading or discharged by looking out across Swansea Bay from the Mumbles Road where the trams used to run many years ago.

A considerable number of years ago I became involved with the BBC Wales World War 2 People’s Project and interviewed a number of Cardiff RNIB Blind and sight handicapped members with their stories being used by the South Wales Talking Magazine Association.

For many years, I was the Hon Welfare Officer and member of the Merchant Navy Association (Wales) and feel it is respectfully fitting to end this story based on some of my seagoing experiences by stating that each year we hold a service at the Seafarers Memorial which is a large steel model of the structure of a wrecked ship’s hull with the feature of a person’s head at the bottom of the hull. The memorial is situated by the Senedd, overlooking Cardiff Bay. The first part of the oration says, “Let us dedicate a moment of silence to all our shipmates in the Merchant Navy, the fishing Fleets and Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service who, in Peace and War go down to sea in ships on deep waters never to return.”

In December 1975 the 227,556-ton oil and ore bulk carrier Berg Istra, sailing under a Liberian Flag, blew up in the Moluccas Sea and was entered in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest vessel to become a total loss. Only a few people knew about her sinking with no one being able to explain the cause of her loss. Such ships were the start of the big ships like the MV Derbyshire, lost in a typhoon to the south of Japan in 1980.

In the 20 years following the loss of the Berg Istra about 340 large bulk carriers were lost at sea,

Taking with them 1,300 lives.

END

June 2018

HEROES - By DAVID PARTRIDGE

The following poem was read at the Raising of the Red Ensign at the Mansion House, Cardiff, by Gilbert Lloyd, High Sheriff of South Glamorgan, on Saturday 1st September 2017. The members present were so impressed with it that we decided to include it on our website.

Don’t speak to me of heroes until you’ve heard the tale

of Britain’s merchant seamen who sailed through storm and gale

to keep those lifelines open in our hour of need

when a tyrant cast a shadow across our Island breed.

Captains, greasers, cabin boys, mates and engineers

heard the call to duty cast aside their fears

They stoked those hungry boilers and stood behind the wheel

while cooks and steward manned the guns on coffins made of steel

They moved in icy convoys from Scapa to Murmansk

and across the western ocean, never seeking thanks.

They sailed the South Atlantic where raiders lay in wait

and kept the food lines open from Malta to the Cape.

Tracked by silent U-boats which hunted from below

shelled by mighty canons and fighter’s flying low.

They clung to burning lifeboats when the sea had turned to flame

and watched their ship mates disappear to ever lasting fame.

I speak not of a handful but 30,000 plus, some whose names

we’ll never know in whom we placed our trust.

They never knew the honour of medals on their chests

or marching bands and victory and glory and the rest.

The ocean is their resting place, their tombstone is the wind

the seabird’s cry their last goodbye to family and friend.

Freighters, troopships, liners and tankers by the score.

Fishing boats and coasters, 2000 ships and more.

They flew the Red Duster as they sank beneath the waves

and took those countless heroes to lonely ocean graves.

Their legacy is freedom to those who hold it dear

to walk with clear horizons and never hide in fear.

So when you speak of heroes remember those at sea

from Britain’s Merchant Navy who died to keep us free.

SEPTEMBER 2017

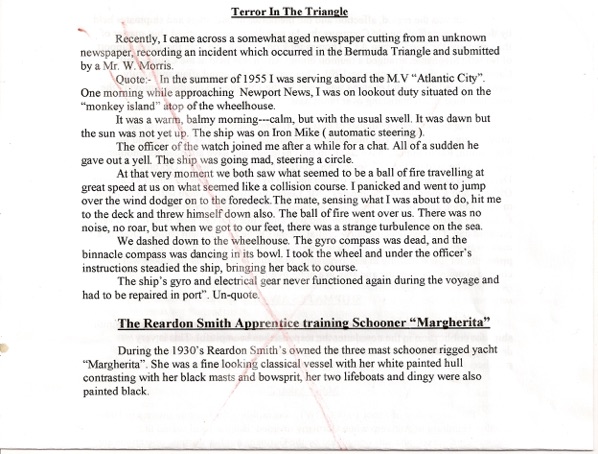

A couple of items submitted by Commodore Oliver Lindsay

August 2015.

A VOYAGE ON THE S.S. BARON GRAHAM

BY JOE NORTON

I signed on the S.S. Baron Graham as Galley Boy at Greenock on the 28th July 1943. After discharging a cargo of sugar we went up to Glasgow where we spent some time getting extra guns fitted including a “pillar box”. This was a dome shaped contraption with ten rockets either side. After leaving the Clyde our next stop was Penarth. Shore leave was forbidden, but being local, myself and another Barry boy were allowed to go home for a few hours. This was appreciated except for the fact that I had to walk from Barry to Penarth as the last bus was full. In Penarth we loaded army trucks on deck, plus their drivers and mechanics. We sailed for the Solent where we spent 14 days swinging around the hook, but we did get one night ashore. Early one evening we noticed a lot of activity. Naval tenders were approaching the 14 cargo ships which had now assembled. They were carrying DEMS gunners to man the extra guns that had been fitted.

Later in the evening we raised the hook and set off in convoy with a naval escort. We were ordered to muster on the forward well deck at 7.30 p.m. when we were told that we were to sail along the French coast in the hope that the Germans would send out their planes to attack us and the RAF would come and shoot the Germans down. Fortunately nothing happened. At the time we had over 100 people onboard as did the other ships. What carnage could have occurred. We headed for Swansea where we unloaded the trucks and excess gunners and drivers. We spent several days in Swansea loading coal and then sailed for Milford Haven to join a convoy.

Eventually we left Milford and headed off into the unknown. After several days we developed engine trouble and had to drop out of the convoy. One of the escorts circled us while the problem was being sorted and we then rejoined the convoy. Unfortunately we had to drop out again but this time the escort was not so friendly. The message was “the convoy must go on. Goodbye and good luck”. Things were going alright until one morning when a plane was spotted approaching from head on. It was flying low from fore to aft and the Swastika and the German Cross told us that it was not a friend. We could actually see the crew pointing at us. It flew astern of us, turned and started it’s bombing run. It was then that our gunners opened up with the rockets. The plane veered to port and disappeared. It did not return. We sent an attack signal and a British destroyer met us and escorted the ship to Gibraltar. We waited to join another convoy at Gib and ended up in Algiers.

After a week or more in Algiers we set off for Gib for orders. Several days at anchor here, no shore leave, then a convoy of 4 ships set off for Huelva in Spain. Quite pleasant steaming up the Spanish coast within the sight of land. Had a nice time in Huelva especially in the “pastelaria” (cake shop). Then it was back to Gib to wait for a homeward bound convoy.

After three attempts we were finally on our way home. Unfortunately we were picked up by a spotter plane. Our escort was reinforced, but three days after being sighted by the Spotter plane, the alarm bells rang and the heavy mob arrived. There was a near miss when a bomb hit the water between us and a corvette. A ship in the centre lane was hit and started to burn. Luckily the crew managed to fight it. As dusk descended the raid ended. Things were getting back to normal when the alarm bells sounded again. The u-boats had arrived. The all clear was given a couple of hours later. I read a report of the incident which stated that the convoy was attacked by 25 aircraft. One merchant ship was sunk, an escort vessel damaged and 2 U-boats were also reported sunk.

We eventually arrived in the UK , discharged our cargo in the North East and sailed to Barry for paying off. This was my only taste of war action thank goodness. My war days finished when the S.S. Empire Don, on which I was serving, arrived at Genoa on VE Day.

Joe Norton

December 2014

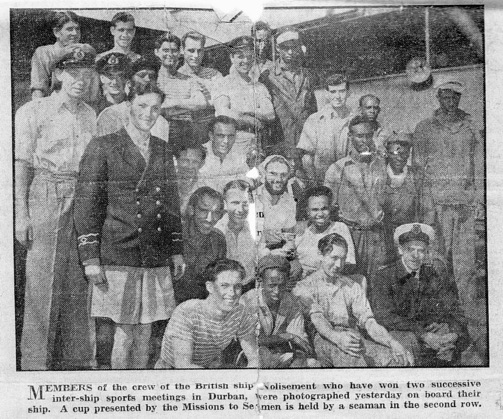

Nolisement Crew Top Athletes in Port Durban

Extract from the Durban Times

“In 1948, the crew of the Nolisement whilst in Port Durban, South Africa, won an inter-ship sports meeting and were presented with a cup from the Missions to Seamen. After their victory they threw out a challenge to any other merchant ship in durgan to try and beat them. The challenge was accepted by teams from Southmoor, Sculptor, Richmond Castle, Fort Highfield, Lawhill, Miendore and Waimana.

The meeting was organised by the Mission to Seamen and took place at Albert Park. The events included distance races, relay races, a tug-of-war, A wheel barrow race, a potato race and a chariot race. The crew of the Nolisment ran oput easy winners fully justifying their challenge. The crew of the wind-jammer Lawhill obtained second place , while the Southmoor was third. The best all -round performer proved to be Chris Halls, a member of the Lawhill’s crew. He won the mile, and quarter-mile race and also got a place in other events. In all , about 100 competitors took part in the meeting and there were 21 in the winning team from Nolisement.

As well as winning two successive inter-ship sports meetings, the crew of the Nolisement have also distinguished themselves at soccer. During the three weeks the ship has been in Durban, they have played nine games and have only been defeated once by a team from City of Exeter.

One of the Nolisement’s officers said that the crew of the ship were all keen on sport and always participated in those ports where sport was organised. They had always been able to hold their own.”

A member of the winning team was none other than our own Joe Norton who is third from the left in the back row of photograph.

January 2012

LOSS OF THE GERMANIC

(Photo Courtesy of Library of Contemporary History, Stuttgart)

On returning from Halifax in convoy HX-115, the Germanic (Skipper now Richard Mortimer) was torpedoed and sunk about 200 miles south of the southwest tip of Iceland, on the 29th March. It is believed to be the most northerly torpedoing in the Battle of the Atlantic, from 1939 to 1943. Five members of the crew were killed. Fortunately for us an HM corvette (HMS Dianella) had lost its asdic and was allowed to call off chasing u-boats and proceed to rescue survivors. Germanic was loaded with grain and did not sink for about six hours when the grain swelled and finally burst the hull wide open, We were taken to Londonderry and then by ferry to the UK. During the six hours in the lifeboat one survivor, the ship's second engineer, apparently not injured, kept moaning and asking for water. The rest of the survivors were quite sympathetic but tended to be a little annoyed why an uninjured person should make such fuss.

Later the corvette's medic explained to us that the second engineer had suffered a piece of shrapnel slicing his scrotum in two. He was dealt with separately from the uninjured survivors so I do not know what happened to him. Being a radio officer I was also the morse lamp signaller, when the corvette approached our lifeboat it flashed 'what ship', I replied 'Germanic'. Later on when we were all rescued and on board the corvette one officer told us ' you are lucky, one gunner wanted to fill the lifeboat with machine gun bullets as soon as 'German' was signalled.

Colston Hicks, 2nd Radio Officer.

Mem. No. 191

Murder at Breakfast

The 16th August 1959 found the M.S. New Westminster City berthed below the cliffs at Rosario, on the River Parana, loading general cargo which included several large parcels of bagged sunflower expellers.

The second day of loading opened sunny and mild, a beautiful winter morning and a promise of a good loading day. At about 0740 hours the stevedores led by their foreman and his son descended the cliff face by means of the steel stairway on the cliff face and strolled the 200 yards or so to the ship’s accommodation ladder. The foreman accompanied by his son started climbing the ship’s ladder followed by the stevedores. One of the stevedores standing on the wharf shouted up to the foreman ”have you ordered extra stitchers for repairing the broken bags containing expellers?”. The foreman with a wave of his hand dismissed the question, for which he paid with his life. In the hand of the stevedore on the wharf appeared a pistol, he fired two shots, the first struck the foreman in the head and he died instantly on the gangway, the second shot fatally wounded the foreman’s son who fell from the gangway onto the wharf and died two hours later in hospital. The murderer turned and ran to the cliff and ascended the stairway and disappeared. Soon police, doctor and ambulances arrived and attended to the incident formalities.

At the time of the incident I was standing at the top of the gangway waiting for the foreman to board to discuss stowage, rather too close to the victims for comfort.

Normality was soon restored. The gangway seacunny for the second time within an hour scrubbed the accommodation ladder down to remove the blood etc. The ensign was lowered to fly at half mast. The butler beat the gong for a late breakfast. No loading was performed for the next two days out of respect for the two men who had died.

Up to the time of sailing the murderer had not been found, however I learnt from officials that twelve months previously he shot and killed another man. Apparently he was a member of a wealthy family who paid a very substantial fine in lieu of a long jail sentence for homicide.

Some readers may well remember Rosario and the berths under the cliffs.

Commodore Oliver Lindsay, Mem No. 4.

Superintendent’s Luck

It was the summer of 1952, the S.S. Tacoma City, Master Captain R.E. Shilstone, was in Barry loading a cargo of coal for Buenos Aires. It was a Saturday and pleasant apart from clouds of coal dust from the three tips working the vessel. However, the crew could look forward to a peaceful afternoon as it was traditional for all loading to cease at 1200 hours on a Saturday in South Wales ports so that the coal trimmers and those working on the coal tips could if they so wished enjoy the national game of rugby union.

That morning the attending Marine Superintendent instructed one of the apprentices to go into the pantry where the Chief Steward was waiting with a carton (rationing was still on) and place the carton in the unlocked boot of his car, a black Austin which was parked on the far side of the quayside rail tracks and safely clear of any rail track operations. The apprentice did exactly as instructed. After lunch the lad was approached by an Irate Superintendent who on checking the boot of his car found no carton. The lad insisted that he had taken the carton ashore and stowed it in the boot of a black Austin car. They both went to the gangway and looked across at the car, the lad looked at the Superintendent and said “ Sir you have shifted your car a little, When I placed the carton in the boot it was parked abreast of the gangway” Christmas arrived early in 1952 for the unknown owner of a black Austin car whose boot also happened to be unlocked.

Later in the afternoon, the superintendent having past the risk of apoplexy but now with greasy hands, sought out the same apprentice again, whose day aboard it happened to be, to obtain some paraffin from the lamp locker. Whilst they were in the locker getting the paraffin the superintendent noticed there were a surprising number of full two gallon cans of Esso. Petrol being rationed and his car petrol tank low he told the apprentice to take one of the cans and pour it into his car’s tank and he would inform the Mate so he will be aware of the matter, and then added “make sure you get the right car this time. The apprentice said “aye aye Sir”.

About an hour later the superintendent disembarked to motor home - you may have guessed it - the car would not start. The can contained paraffin. The air became blue but not by car exhaust smoke. The ship having stored in Barry the paraffin tanks had been filled and the surplus placed in the empty Esso petrol cans.

I will leave it to your imagination what was said to the humble apprentice. It was just not the superintendent’s day.

Commodore Oliver Lindsay, Mem No. 4

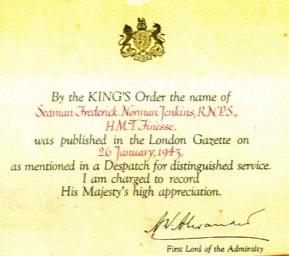

First Trip

of

Fredrick Norman Jenkins

On the 4th May 1940 the S.S. Graig went ashore on Flint Ledge Egg Island Nova Scotia in fog and was wrecked. All the crew survived with only one injury to the Royal Marine Gunner.

First Trip (Continued)

by

Frederick Norman Jenkins

Here the story continues.

“Our last port of call in South America was Rio de Janeiro then we headed north to our discharge port of Limerick, stopping only at Dakar where we loaded bunkers and also picked up a DBS (Distressed British Seaman). The trip north was uneventful except that after leaving Rio we had a “pampero” a gale force wind which resulted in small birds, which had been blown out to sea, landing on the deck. I picked them up and the only place I could think of putting them was in the Captains bathroom which was rarely used. However he soon found out. On another occasion I fancied some marmalade on my bread and butter but the steward said I would have to ask the Captain. I went up to the bridge just as they were about to take sights. On hearing my request the Captain was not pleased and ordered me off the bridge. As I was repeating my request the steward arrived and the Captain told him to give me the marmalade and never to send me to the bridge again. I enjoyed my bread and butter.

After discharging at Limerick we proceeded to Barry Dock to dry dock as the ship had struck an obstruction and damaged one of the blades of the propellor.. We laid on the buoys and I worked by her, then we loaded cargo for Rosario. We sailed on Friday November 13th 1939 in a strong wind to join a convoy from Milford Haven. We lost the convoy first night out so proceeded to Rosario on our own. Whilst off Rio we heard that the German pocket battleship Graf Spee was doing battle with three H.M. cruisers. My elder brother had left Newport for Buenos Aires in the Trekieve two days before us and was able to witness the fate of the Graf Spee. We arrived later to see the burning wreck.

H.M.R.T. Frisky

During the Second World War, Colston Hicks served as a Radio Officer in the deep sea rescue tugs. Whatever the weather the little rescue tugs could always be relied upon to arrive on the scene when assistance was needed. Times were often hard and dangerous but there were also lighter moments as Colston now reflects.

I will not go into the finer details of the game except to tell you that we lost 64 - 0! The victorious team marched back to town again with the band playing loudly. It only came to light the next day when a shopkeeper told us that the team we had played was a crack Yugoslavian army team, and being a Communist Country it must have been the National team as well. But, what the hell! How many crews of the Rescue Tugs boys do you know that have played international football. I can tell you that the boys of HMRT Frisky dined out on that story for a few years.”

Colston Hicks - Mem. No. 191

Brief Encounter.

For whatever reason the U-boat was operating on the surface one can only surmise, she was obviously as surprised as we were on the Houston City.

A very brief encounter.

Eventually the visibility improved and most of the ships from the dispersed convoy proceeded to a predetermined rendezvous and the convoy reformed and proceeded to Halifax N.S. arriving there without incident on the 29th April 1943.

Commodore O.J. Lindsay, Mem. No. 4

S.S. Baron Elgin - 1946

On the Members Ships page it is reported that four of our Barry members have served in the Baron Elgin. I am pleased to announce that the number has now increased to five. Member John Filer joined the ship in September 1946 as a Senior Ordinary Seaman (SOS) and this is his story of that trip.

On joining Baron Elgin at Barry Dock, I was a little perturbed to find that sailors and the Arab firemen were berthed under the foc’sle head, sailors to starboard, firemen to port. As my first three ships, two Forts, and one Park Type, were wartime built and only three/four years old, the state of the accommodation was disheartening.

Eight bunks, a long mess table and a Bogie stove (good for making toast), plus a number of lockers for your personal belongings. The bathroom, entered from the foredeck, was just a steel box, no showers or freshwater taps, with a shelf to slot your new galvanised bucket into. The one toilet was similar, and quite dangerous to use on the homeward leg of the voyage, when loaded. Probably a towel was provided, but no bed sheets or pillowcases.

As a three island type vessel, her only redeeming feature was her well formed cruiser stern. In my time onboard there was no accommodation block on the poop. The Chippie bunked there in the still remaining DEMS gunners quarters. In bad weather the lookout was kept on the bridge wings. These were also wartime fittings, being previously built as gun tubs. They were only waist high, therefore very exposed to the wind and rain.

Soogying was only carried out when it was raining, the galley pump being locked up most of the voyage. Another antiquity was the icebox alongside number three hatch. It was fortunate we were only away for five weeks, otherwise some of the edibles would be smelling a little.

Our loading port (just the end of a bay) was Springdale, Hall Bay, Newfoundland and consisted of three log cabins and a motor launch. We dropped anchor, swung, with help from the launch, and four stern lines were secured on tree stumps on the shore.

I believe the name of my fellow SOS was Gordon Wilson of Cadoxton. I sailed with Gordon and one of his brothers again in 1951 aboard Palestinian Prince. One AB from the Valleys had brought his weightlifting equipment, and would be out on number one hatch practicing his lifts at every opportunity.

We loaded wood pulp, with some fifteen feet of deck cargo and proceeded to Rochester, Kent where we tied up to the buoys, paying off the following day, weights as well.

It was a further eight years before I had the misfortune to sail on a vessel that also suffered with similar deficiencies. Another story, another time.

John Filer, Mem. No. 24